The Unmakeable Photograph: What a 1950s Street Scene Reveals About Our Digital Future

The Girl in Florence

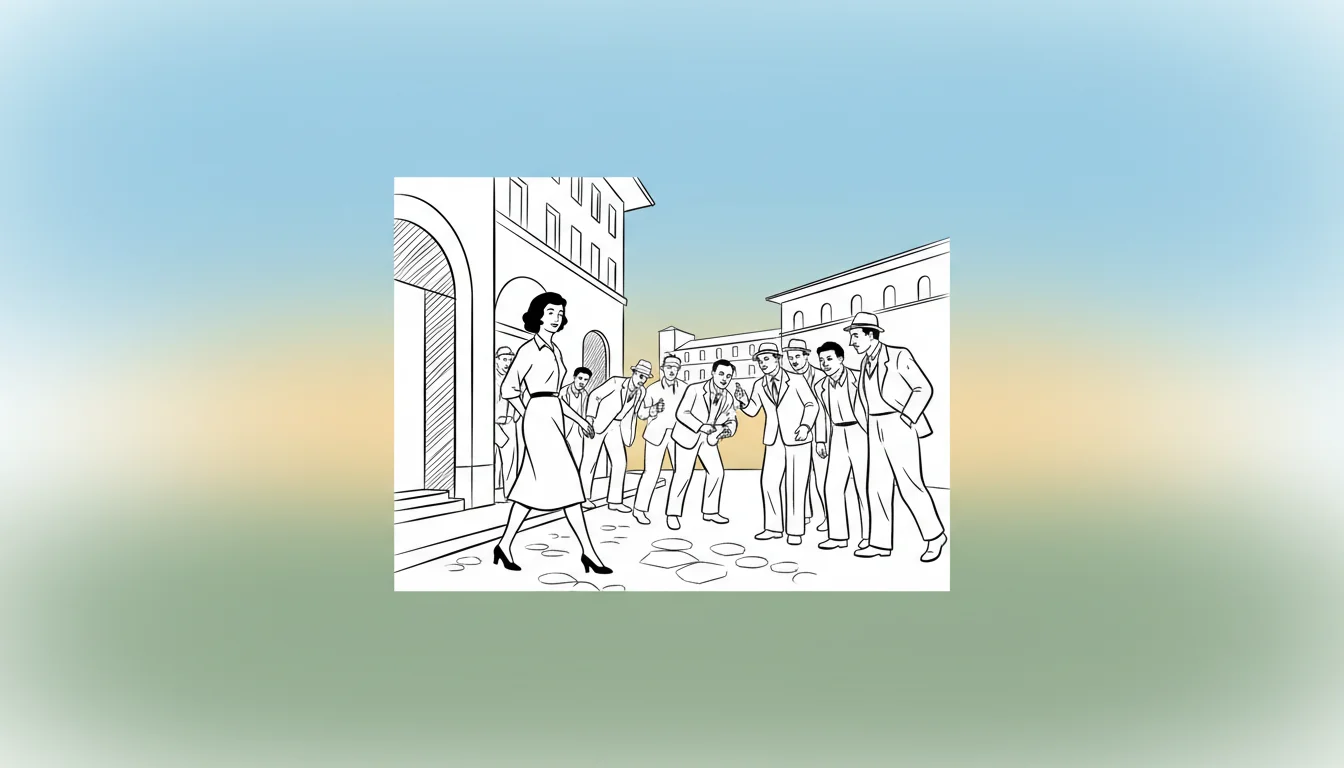

The air in the gallery is still and cool, a deliberate silence that invites you to lean in close. You’re at a Ruth Orkin exhibit, surrounded by large, luminous black-and-white prints that feel less like pictures and more like portals. Your eyes drift from a shot of a child playing in a New York alley to a portrait of a pensive-looking actor, and then they land on it. The one. The photo that seems to vibrate with a life all its own, pulling the entire room into its orbit.

The image is "An American Girl in Italy, 1951." At its center is a young woman, Jinx Allen, who is a supernova of confidence. Her shawl is clutched in one hand, her head is held high, and she strides forward with a purpose that seems to cut right through the frame. But it’s the constellation of men around her that creates the photo’s undeniable gravity. They are a gallery of gawkers, a chorus of reactions frozen in time. One man stares, another grins, a third has his hand on his crotch in a gesture of pure id. The entire scene is a powder keg of ambiguity—is this empowerment or harassment? A moment of confident navigation or a gauntlet of unsolicited attention? It’s electric, uncomfortable, and utterly captivating.

As it turns out, the story behind the photo complicates the narrative. Orkin and Allen (whose real name was Ninalee Craig) were traveling together for a Life magazine assignment on what it was like for a young woman to travel alone in post-war Europe. The shot wasn't a lucky accident. After watching Allen draw attention while walking down a street, Orkin asked her to do it again so she could capture it. For her part, Allen never saw the moment as threatening. She recalled it as fun, a performance. She felt like Dante’s Beatrice, gliding through the streets of Florence, and said, “I was the subject of my own Divine Comedy.” The endless debate over whether the photo was "staged" or "candid," however, misses a far more profound question that hangs in the quiet air of the gallery: Could a photograph like this even be made today?

Anatomy of a Public Moment

To understand why the answer is almost certainly no, you have to deconstruct what makes Orkin's photograph so potent. Even with the photographer's prompt, the image captures a raw, unmediated social dynamic playing out in public. The reactions of the men might be provoked, but they aren’t faked. The photo is a time capsule of an unfiltered public interaction, a moment of street theater where the lines between observer and participant are beautifully, thrillingly blurred.

The scene works because everyone is playing a distinct, unrehearsed role. Jinx Allen is the confident protagonist, owning the space she walks through. The men are the reactive audience, their gazes and gestures providing the story's tension and energy. Ruth Orkin is the unseen observer, capturing the drama without becoming part of it. And the street itself? It’s the stage. This was an era when public space was the primary theater for social life. Before endless streaming options and infinite digital rabbit holes, the sidewalk was where you went to see and be seen, where the messy, unpredictable drama of human interaction unfolded in real-time.

The Ghosts in the Machine

Now, let’s try to stage this scene in 2024. The entire dynamic collapses under the weight of a world remade by technology.

First, consider the subject. Our modern "American Girl" is likely walking with AirPods firmly in place, creating a sonic barrier between herself and the world. Her eyes aren't meeting the gazes of strangers; they’re locked on the screen in her hand. Her posture isn't one of confident engagement but of deliberate unavailability. She isn't performing the role of Beatrice, navigating the city’s energy; she's performing the modern ritual of avoidance, projecting a digital forcefield that says, do not engage.

Next, the onlookers. The men on the corner today exist in a state of ambient surveillance. Every person passing by is holding a high-definition camera, and the fear of becoming the internet’s next "main character" is a powerful deterrent. A casual glance could be recorded, stripped of context, and turned into a viral TikTok shaming them as creeps. This is the panopticon effect in action. The chilling effect of potential public judgment replaces open reaction with guarded self-consciousness. Gazes are averted. Reactions are suppressed. The audience has stage fright.

And finally, there's the photographer. Ruth Orkin’s role as an invisible documentarian is now practically impossible. The moment a professional camera is raised on a city street, the spell is broken. The scene becomes contaminated with awareness. People become suspicious, they pose, or they turn away. The act of photographing strangers is no longer a neutral observation; it’s a fraught transaction laced with questions of privacy, consent, and intent. The authenticity Orkin captured evaporates the instant the modern world notices it’s being watched.

The photograph is unmakeable today not because of any single change, but because the entire operating system of public life has been rewritten. The invisible audience of the internet has become a ghost in the machine, a silent director dictating the behavior of every actor on the street.

When the Sidewalk Became a Feed

The impossibility of Orkin's photo points to a much larger cultural shift: we have all internalized the logic of the social media feed and applied it to our physical lives. Public spaces are no longer just places to be; they are potential backdrops for content, real-life soundstages for our digital identities.

Think about it. We perform our lives for a hypothetical audience that exists somewhere in the cloud. We frame our experiences—our coffee, our outfits, our vacations—not just for the moment, but for their potential shareability. We curate our expressions and our actions in the real world with the same meticulous consideration we’d give to an Instagram post. We are all, to some extent, influencers of our own lives, and the street is our set.

This has fundamentally altered the nature of the "public square." Historically, public space was messy, unpredictable, and wonderfully ephemeral. It was a forum for spontaneous encounters and unscripted moments. Today, the rules of the digital plaza—performance, polarization, and permanence—have bled into our physical world. The result is a landscape that feels increasingly sterile, where genuine, off-the-cuff interaction has become a rare and endangered species.

The High Price of a Perfect Picture

So, what have we lost in this transition? To be clear, this is not an exercise in romanticizing the past or making excuses for the leering and catcalling that women like Jinx Allen undoubtedly endured. It's about mourning the loss of something more subtle, a specific kind of public freedom that has quietly slipped away.

What has vanished is casual anonymity—the freedom to be unobserved, to be awkward, to be lost in thought, to simply exist without the low-grade hum of potential surveillance. The cognitive load of constant, low-level performance and self-monitoring is exhausting. It's the price we pay for a world where every moment is a potential photo op, every interaction a potential piece of content. We have traded the rich, unpredictable texture of unscripted moments for the glossy, shareable, and ultimately hollow polish of a perfect picture.

Walking Through Florence, Again

Standing back in that quiet gallery, you look one last time at the girl in Florence. You think of Jinx Allen’s beautiful framing of the moment: she was Beatrice, performing her own Divine Comedy. Her performance was for a specific audience on a specific corner on a specific afternoon in 1951. It was contained, immediate, and real.

Today, we are all actors in a different kind of Divine Comedy. We navigate the digital inferno of potential cancellation, the lonely purgatory of perpetual self-awareness, and the exhausting quest for the curated heaven of our online profiles. It is a performance for an invisible, unknowable audience, and it never, ever ends. Looking at the raw, kinetic energy of that 1951 photograph, you have to ask if this new reality truly constitutes progress. Perhaps the future of our digital lives isn't about finding new ways to perform, but about remembering how to simply walk through the city again—not as content for a feed, but just for ourselves.

Antriksh Tewari

Head of Digital Marketing

Antriksh is a seasoned Head of Digital Marketing with 10+ years of experience who drives growth across digital, technology, BPO, and back-office operations. With deep expertise in analytics, marketing strategy, and emerging technologies, he specializes in building proof-of-concept solutions and transforming them into scalable services and in-house capabilities. Passionate about data-driven innovation, Antriksh focuses on uncovering new opportunities that deliver measurable business impact.