Your UX Research is a Lie

Let’s start with a hard truth, the kind that makes designers shift uncomfortably in their Aeron chairs and product managers suddenly find the ceiling fascinating. A huge portion of your user research—the stuff you use to justify your roadmap and validate your designs—is probably a well-intentioned, beautifully documented, and incredibly expensive lie. It’s a bitter pill to swallow, but deep down, you’ve probably suspected it. You’ve felt that nagging doubt after a long day of interviews, a sense that you gathered a lot of words but very little truth.

The problem isn't that you're bad at research. The problem is that you're participating in a ritual that only looks like research. We'll call it performative interviewing. It's the art of going through the motions: you schedule the calls, you write the script, you talk to the users, you synthesize the notes, and you present the findings. Check, check, check. Everyone feels productive. But at the end of the day, this ritual consumes your team's most valuable resources—time, focus, and money—without meaningfully changing the product's direction. It's a box-ticking exercise that provides a warm blanket of false confidence.

If you’ve ever walked out of a user interview, turned to your team, and said, “Hmm… interesting,” only to go back to your desk and build the exact feature you were already planning to build, then you know this feeling intimately. You’ve been a part of the performance. This isn't just a waste of an afternoon; it’s a dangerous delusion. It’s a productivity-sucking lie that convinces smart teams they have customer validation, leading them to confidently build the wrong thing.

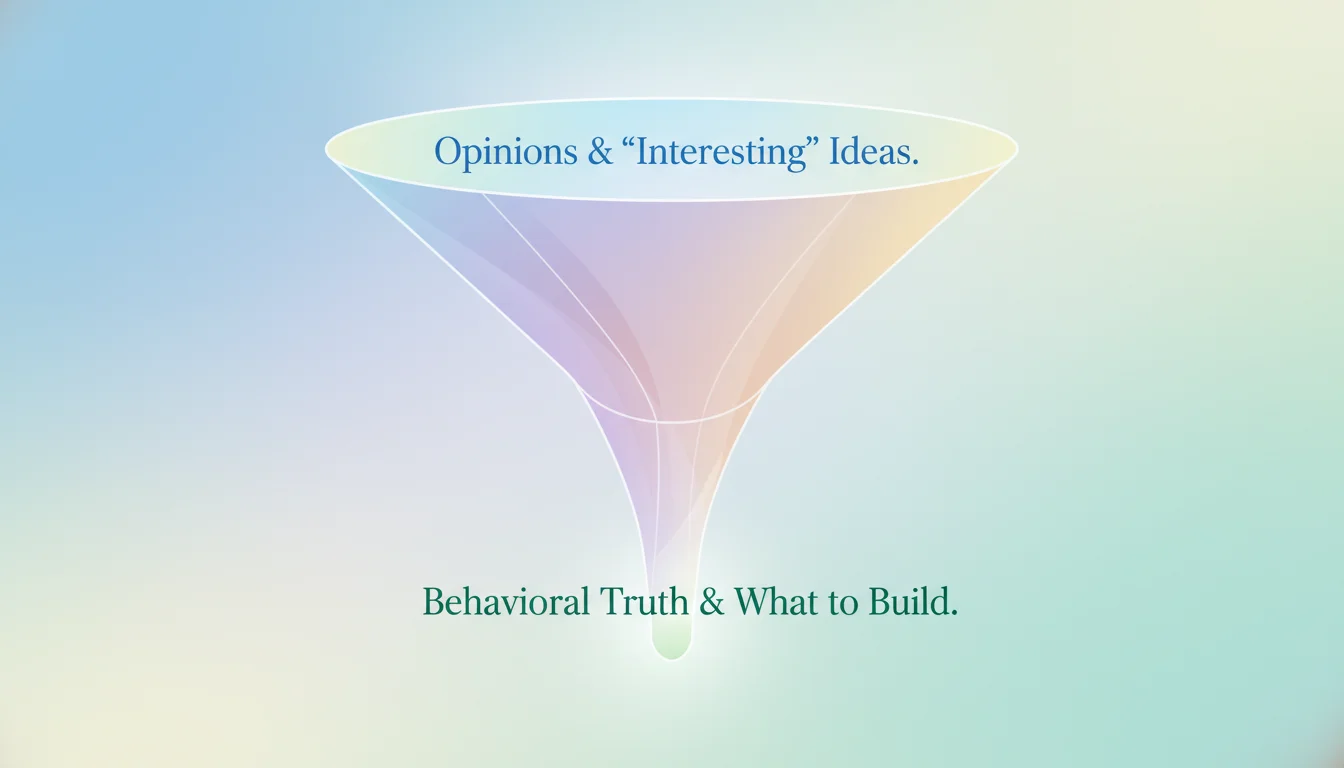

Opinions are Cheap, Behavior is Gold

The entire charade of performative research is built on one fundamentally flawed foundation: asking people for their opinions about the future. We treat our users like fortune tellers, expecting them to gaze into a crystal ball and tell us exactly how they’ll behave.

The Fortune Teller Fallacy

Here’s the biggest mistake in UX research: we ask people to predict their future actions, and we actually believe their answers. People are terrible at predicting their own behavior, but they are absolutely fantastic at telling you what they think they’d do, or more accurately, what they think you want to hear. Their answers are a cocktail of good intentions, wishful thinking, and a desire to be helpful.

Think about it this way: ask someone on January 1st how many times they plan on going to the gym that year. They'll give you an optimistic, well-intentioned, and completely fabricated number. They genuinely believe they'll go three times a week. But if you want the truth, you don't ask about their New Year's resolution; you look at their credit card statement from last year to see how many times they actually paid for a gym they never went to. One is an opinion, the other is a behavioral fact.

This is why the question, "Would you use this?" is the single most useless question in our field. The answer is almost always a polite "yes," "maybe," or "yeah, that looks cool." This response gives you a fleeting hit of validation but provides exactly zero valuable data. It’s the sugar high of user research—it feels good for a moment, then leaves you with nothing.

The Politeness Trap

So why do users mislead us? It's not because they're malicious. It's because they're human. When you sit a user down and show them your mockups, you’ve created a social dynamic with unwritten rules. They instinctively know you’ve poured hours of work into this. They see your designs as your "baby," and nobody wants to be the person who tells you your baby is ugly.

They want to be helpful. They don't want to hurt your feelings. They definitely don't want to sound stupid or uncooperative. This is a well-documented phenomenon known as social desirability bias. In simple terms, people are psychologically wired to give answers that make them look good, smart, and agreeable. Your interview setting is a powerful amplifier for this bias. They aren't lying to you maliciously; they are conforming to social pressure you created the moment you asked, "So, what do you think of our amazing new feature?"

Confessions of a Performative Interviewer

Okay, let's turn the lens on ourselves. This isn't about shaming anyone—we've all been there. Recognizing the patterns is the first step to breaking them. See if any of these "confessions" sound a little too familiar.

You might be a performative interviewer if you find yourself leading with the demo instead of the discovery. You spend the first ten minutes of the call walking the user through your brilliant Figma prototype, explaining every clever interaction. Then, after you’ve thoroughly biased them with your solution, you finally ask, "So… what do you think?" At this point, you're not conducting research; you're just a salesperson seeking applause. You’re asking them to critique your solution to a problem you haven’t even established they actually have.

You're also deep in the performance if your script is a land of hypotheticals. Are your questions littered with phrases like, "Imagine if you had a feature that could..." or "What if you were able to...?" These questions don't uncover reality; they generate fantasy. You're co-writing a science fiction story with your user, and while it might be a fun creative exercise, it has no bearing on what they will actually do when faced with a choice in the real world.

Finally, the biggest red flag is the confirmation bias high-five. This is that little thrill you get when a user says something that perfectly aligns with a slide in your pitch deck. You furiously highlight that quote, bold it in your notes, and present it as the "voice of the customer." Meanwhile, any data that contradicts your hypothesis is quietly dismissed as an "outlier" or a user who "just didn't get it." If your final research report is just a highlight reel of validation and the feedback never sparks a heated debate or forces you to kill a feature, you didn't do research. You went looking for compliments.

Stop Asking Questions, Start Hunting for Stories

So, how do we fix this? The solution is a fundamental paradigm shift. Your goal is no longer to ask better questions. It's to stop asking for opinions and predictions altogether. You must become a detective, not an interviewer. You are no longer seeking validation; you are hunting for hard evidence of past behavior.

The Time Machine Technique

The golden rule is simple: Ask about the past, not the future. Instead of asking users to predict what they would do, prompt them to tell you a specific story about something they have already done. The past is a rich source of facts, emotions, and struggles. The future is just a guess.

- Before: "Would you use an app to manage all your subscriptions?" (This is a hypothetical question that invites a meaningless "yes.")

- After: "Tell me about the last time you tried to cancel a subscription. Walk me through it, step-by-step, from the moment you decided to cancel. What was the hardest part?" (This is a story prompt that uncovers real pain points, workarounds, and emotions.)

The second prompt doesn't get you an opinion. It gets you a story. In that story, you’ll find the truth: the frustration of hunting for a hidden "cancel" button, the workaround of calling their credit card company, the relief they felt when it was over. That is the raw material of a product people will actually pay for.

Follow the Money (or the Clicks)

The strongest evidence of a problem's importance is commitment. Has the user ever invested their own resources—time, money, or energy—to solve this problem? Past behavior is potent, but past behavior that involved a cost is gold.

Your new job is to hunt for that evidence with targeted prompts:

- "How are you solving this problem for yourself right now?"

- "Walk me through your current process."

- "Have you ever paid for a tool or service to try and fix this?"

- "What have you tried in the past that didn't work out?"

If they're not currently doing anything to solve the problem, it's probably not that important to them, no matter how much they say they love your hypothetical solution. But if they show you a cobbled-together spreadsheet, tell you about three apps they tried and abandoned, or describe a frustrating two-hour phone call, you've found a real, validated pain point.

The Art of the Awkward Silence

Here’s one of the most powerful and uncomfortable techniques you can learn: ask a story-based question, and then shut up. As humans, we are desperate to fill the silence. As interviewers, we rush to rephrase the question or offer suggestions. Don't. Let the silence hang there. The user will feel the pressure to fill it, and what comes out is often the most valuable, unscripted, and honest part of the entire interview. It’s in the pause after "Walk me through that..." that the real story begins.

From "Interesting" to Indispensable

The shift from a performative interviewer asking for opinions to a behavioral researcher hunting for stories is the single most important leap you can make. It’s the difference between seeking validation and seeking truth. It’s trading the cheap comfort of hearing people agree with you for the invaluable, game-changing insights that come from understanding their reality.

Real UX research isn't about proving you're right. It's about earning the right to build anything at all. It is the single most effective tool you have for de-risking your roadmap, killing bad ideas before they consume a single line of code, and focusing your team’s precious energy on problems that actually matter.

So, the next time you're preparing for a user interview, I challenge you to change your goal. Your goal is not to walk out of that meeting and say, "Hmm… interesting." Your goal is to walk out ready to say, "We were wrong about everything. And now we know exactly what to build."

Antriksh Tewari

Head of Digital Marketing

Antriksh is a seasoned Head of Digital Marketing with 10+ years of experience who drives growth across digital, technology, BPO, and back-office operations. With deep expertise in analytics, marketing strategy, and emerging technologies, he specializes in building proof-of-concept solutions and transforming them into scalable services and in-house capabilities. Passionate about data-driven innovation, Antriksh focuses on uncovering new opportunities that deliver measurable business impact.